What is racing's "Social Licence" and what does this mean?

/Paull Khan expands upon a presentation he gave at the

European Parliament to the MEP’s Horse Group on November 30th

As World Horse Welfare recently pointed out in its excellent review of the subject—while social licence or the ongoing acceptance or approval of society may be ‘intangible, implicit and somewhat fluid’—an industry or activity loses this precious conferment at its peril. Examples, all too close to home, can be seen in greyhound racing in Australia and America or jumps racing in Australia.

What is clear is that our industry is acutely aware of the issue – as are our sister disciplines. The forthcoming Asian Racing Conference in Melbourne in February will feature a session examining what is being done to ‘ensure that (our) a sport is meeting society’s rapidly evolving expectations around welfare and integrity’. And back in November, the Federation Equestre Internationale (FEI) held a General Assembly whose ‘overriding theme’ was ‘that of social licence, and the importance for all stakeholders to understand the pressing needs for our sport to adapt and monitor the opinions of those around us’.

Considered at that meeting were results of a survey, which indicated that two-thirds of the public do not believe horses enjoy being used in sport and have concerns about their use. Those concerns mainly revolve around the welfare and safety of the horses. Intriguingly, a parallel survey of those with an active involvement in equestrian sport revealed that as many as half of this group even did not believe horses enjoyed their sport; and an even higher proportion than the general public—three-quarters—had concerns about their use.

While it is likely true, to an extent at least, that the public tends not to distinguish between equestrian sports, the specific concerns about horse racing are certainly different from those about Olympic equestrian disciplines, which centre on such matters as bits, bridles, spurs and nosebands.

Upon what, then, does our social licence in European horse racing critically depend? What are the major issues about which the public has opinions or worries, and on which the continuance of our social licence may hang? It should be said at the outset that what follows is not based upon scientific evidence (and the research should certainly be undertaken) but merely reflects the belief of the author. But it is suggested with some confidence that the following (in no particular order) are the three issues uppermost in public consciousness. They are:

Use of the whip

Racecourse injuries/fatalities

Aftercare – the fate of retired racehorses

There are, of course, other matters – the misuse of drugs and medications, gambling harms, etc., but the three topics above seem to account for a large proportion of the public’s anxieties about racing. There are likely to be subtle differences in the views of the public between one European country and another. Certainly, it is true that the volume of public disquiet varies very considerably between nations. In Scandinavia and Great Britain, for example, horse welfare and animal welfare more generally are very much front of mind and near the centre of public discourse. It is far less evident in several other countries.

But it is illuminating to look at what racing has been doing in recent years in the three areas listed above, and what the future looks like. A survey was conducted among member countries of the European and Mediterranean Horseracing Federation (EMHF); and it is clear that, while there is much still to be done, there has been significant and sustained progress and good reason to believe that this is likely to continue – and in fact accelerate – over the next few years.

Use of the whip

Let us consider whip use first. At the most recent World Horse Welfare Annual Conference in London in November, straplined ‘When Does Use Become Abuse’, one speaker was called upon to give strategic advice as to how to counter negative perceptions of equestrianism.

What he decided to major on was striking. With the whole breadth of the equine sector from which to draw, he chose to hone in on horseracing and—more specifically yet—on the issue of whip use. It was a salutary further example of how, while the whip may be a tiresome distraction to many, it is front and centre in the minds of many of the public.

Is there any more emotive or divisive issue within racing than the whip? Admittedly, most racing professionals hold that it really is very difficult to hurt a horse with the mandated padded crops, even if one wanted to. And, with veterinary supervision at all tracks, it is impossible to get away with, even if one did. In brief, they don’t consider this a welfare issue, but rather one of public perception.

But it is then that the divisions set in. Some conclude that all that is necessary to do has been done, and that any further restriction on the whip’s use would constitute pandering to an ignorant public. Others argue that, even if it is just a matter of public perception and the horses are not being hurt or abused, the sight of an animal being struck by a human is now anathema to increasingly broad swathes of society—in a similar way to the sight of a child being struck by an adult: a commonplace 50 years ago, but rare today. Therefore, the sport must act to be ahead of the curve of public sentiment in order to preserve its social licence.

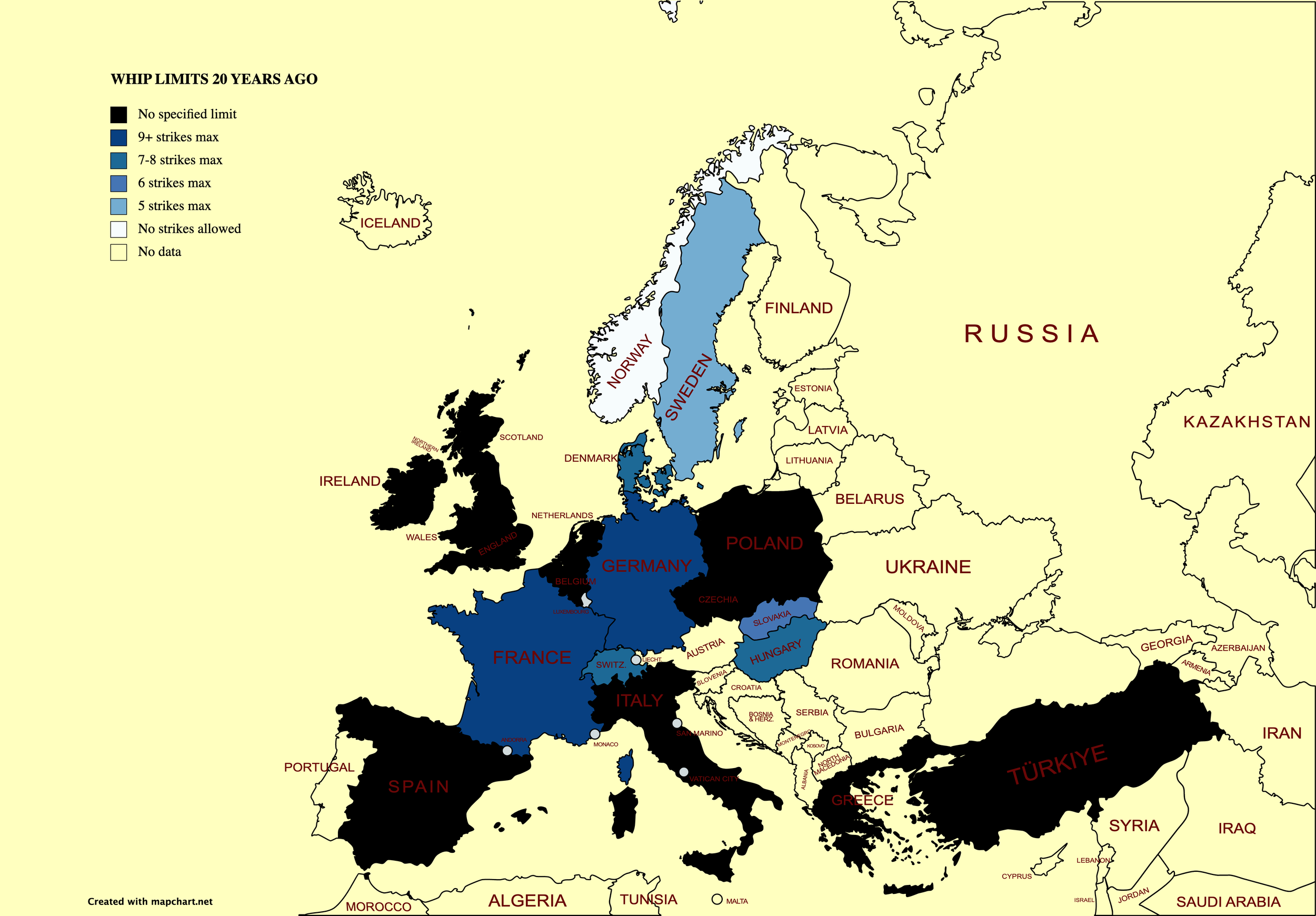

How is this argument playing out? Let us look at a key element of the Rules of Racing in 18 European racing nations—the maximum number of strikes allowed in a race is a blunt measure, indeed, and one that takes no account of other variables such as the penalty regime for transgressions, but one that, nonetheless, paints a telling picture.

The first map shows how things stood 20 years ago. The majority of the countries are shown in black, denoting that there was no specified limit to the number of strikes. Just one appears in white – Norway banned the use of the whip as long ago as 1986.

The second paints the picture as it was 10 years ago. Eleven of the 18 countries had, in the intervening decade, changed their rules and applied a lower maximum number of strikes, and are shown in a lighter colour as a result.

Today’s situation is shown in the third map. All but one of the countries (excluding Norway) have tightened up their whip use rules still further over the past decade. None now allows unlimited use, and countries now banning the use of the whip for encouragement, number four.

It can be concluded that all countries across Europe are moving towards more restricted use of the whip. At different speeds and from different starting points, the direction of travel is common.

What will the situation be in another 10 years? Many administrators within EMHF countries, when asked to speculate on this, gave the view that there would be no whip tolerance within ten years and that the Scandinavian approach will have been adopted.

On the other hand, Britain has recently concluded that the biggest public consultation on the subject and the new rules that are being introduced do not include a reduction in the number of strikes, but rather a series of other measures, including the possible disqualification of the horse and importantly, the requirement only to use the whip in the less visually offensive backhand position.

Whether or not we will see a total ban within the next decade, it must be long odds-on that restrictions on whip use, across the continent, will be stricter again than they are today.

Aftercare

Twenty years ago, little thought was given to the subject of aftercare. There were some honourable exceptions: in Greece, the Jockey Club required its owners to declare if they could no longer provide for their horse, in which case it was placed in the care of an Animal Welfare organisation. Portugal had a similar reference in its Code. Most tellingly, in Britain a trail-blazing charity, Retraining of Racehorses (RoR), had been launched, following a review by the former British Horseracing Board.

Ten years ago, RoR had nearly 10,000 horses registered, had developed a national programme of competitions and events in other equestrian disciplines, and was holding parades at race-meeting to showcase the abilities of former racehorses to enter new careers.

Di Arbuthnot, RoR’s chief executive, explains, “In the UK, a programme of activities for thoroughbreds had started to encourage more owner/riders to take on former racehorses. This was supported by regional volunteers arranging educational help with workshops, clinics and camps to help the retraining process. Other countries were looking at this to see if similar ideas would work in Europe and beyond.

“Racing’s regulators had begun to think that this was an area they should be looking to help; retraining operators and charities that specialised in thoroughbreds were becoming recognised and supported; and classes at equestrian events began in some countries. Owner/riders were looking to take on a thoroughbred in place of other breeds to compete or as a pleasure horse; the popularity of the thoroughbred was growing, not just by professional riders to use in equestrian disciplines, but also by amateurs to take on, care for and enjoy the many attributes of former racehorses.

“The aftercare of the thoroughbred was on the move.”

But not a great deal else was different in the European aftercare landscape.

Since then, however, there has been little short of an explosion of aftercare initiatives. In 2016, the International Forum for the Aftercare of Racehorses (IFAR) was born, “to advocate for the lifetime care of retired racehorses, to increase awareness within the international racing community of this important responsibility.” In this endeavour, IFAR is not in any way facing resistance from Racing Authorities – far from it. It is pushing against an open door.

The International Federation of Horseracing Authorities has, as one of its twelve objectives, the promotion of aftercare standards. And the chair of its Welfare Committee, Jamie Stier, said some years ago that there is ‘now a better understanding and greater recognition that our shared responsibility for the welfare of racehorses extends beyond their career on the racetrack’.

This direction from the top has been picked up and is increasingly being put into active practice. Also in 2016, France launched its own official charity Au Dela des Pistes, (‘beyond the racetrack’), in 2020 Ireland followed suit with Treo Eile (‘another direction’). By 2019, in Britain, remarkably, many more thoroughbreds were taking part in dressage than running in steeplechases!

So now the three main thoroughbred racing nations in Europe all have active and established aftercare programmes; and many other smaller racing nations are moving in that direction. It is not just a matter of repurposing in other equestrian pursuits – many of those horses retiring from racing that are not suited to competitive second careers are simply re-homed in retirement and others find profitable work in areas such as Equine Assisted Therapy.

Arbuthnot (also chair of IFAR) adds: “For racing to continue as we know it, we must assure the general public, those that enjoy racing, that thoroughbreds are not discarded when their racing days are over and that they are looked after and have the chance of a second career. It is up to all of us around the world to show that we care what happens to these horses wherever their racing days end and show respect to the thoroughbred that has given us enjoyment during their racing career, whether successful or not on the racecourse. If we do this, we help ensure that horse racing continues in our lifetime and beyond.”

It is important to publicise and promote the aftercare agenda, and the EMHF gives IFAR a standing platform at its General Assembly meetings. EMHF members have translated the IFAR ‘Tool Kit’—for Racing Authorities keen to adopt best practice—into several different European languages.

Time Down Under and Justine Armstrong-Small: Time Down Under failed to beat a single horse in three starts but following his retirement from racing, he has reinvented himself, including winning the prestigious showing title of Tattersalls Elite Champion at Hickstead in June 2022. Images courtesy of Hannah Cole Photography.

British racing recently established an independently chaired Horse Welfare Board. In 2020, the Board published its strategy ‘A Life Well Lived’, whose recommendations included collective lifetime responsibility for the horse, incorporating traceability across the lifetimes of horses bred for racing.

Traceability will be key to future progress, and initiatives such as the electronic equine passport, which has been deployed among all thoroughbreds in Ireland and Britain, will play a vital part. Thoroughbred Stud Book birth records are impeccable, and we know the exact number of foals registered throughout this continent and beyond. The aim must be to establish the systems that enable us to ascertain, and then quantify the fate of each, at the least until their first port of call after retirement from racing.

Racecourse injuries

There can be nothing more distressing – for racing professionals and casual observers alike – than to see a horse break down. The importance of minimising racecourse injuries—and, worse still, fatalities—is something everyone agrees upon. What is changing, though, it would appear, is the potential for scientific advances to have a significant beneficial effect.

Of course, accidents can and do befall horses anywhere and they can never be eliminated entirely from sport. But doing what we can to mitigate risk is our ethical duty, and effectively publicising what we have done and continue to do may be a requirement for our continued social licence.

There is much that can be said. It is possible to point to a large number of measures that have been taken over recent years, with these amongst them:

Better watering and abandonment of jump racing if ground is hard

Cessation of jump racing on all-weather tracks

Cessation of jump racing on the snow

Safer design, construction and siting of obstacles

By-passing of obstacles in low sunlight

Colouring of obstacles in line with equine sight (orange to white)

Heightened scrutiny of inappropriate use of analgesics

Increased prevalence of pre-race veterinary examinations, with withdrawal of horses if necessary

The outlawing of pin-firing, chemical castration, blistering and blood-letting

Abandonment of racing in extreme hot weather

Many of the above relate to jump racing, and Britain has witnessed a reduction of 20% in jump fatality rates over the past 20 years. But there is more that must be done, and a lot of work is indeed being done in this space around the world.

One of the most exciting recent developments is the design and deployment of ground-breaking fracture support kits which were distributed early in 2022 to every racecourse in Britain.

Compression boots suitable for all forelimb fractures

By common consent, they represent a big step forward – they are foam-lined and made of a rigid glass reinforced plastic shell; they’re easily and securely applied, adjustable for varying sizes of hoof, etc. They reduce pain and anxiety, restrict movement which could do further damage, and allow the horse to be transported by horse ambulance to veterinary facilities.

X-rays can then be taken through these boots, allowing diagnosis and appropriate treatment. These kits have proved their worth already: they were used on 14 occasions between April and December last year, and it would appear that no fewer than four of these horses have not only recovered but are in fine shape to continue their careers. It is easy to envisage these or similar aids being ubiquitous across European racetracks in the near future.

Modular splints suitable for slab fractures of carpal bones

Perhaps of greatest interest and promise are those developments which are predictive in nature, and which seek to identify the propensity for future problems in horses.

Around the world, there are advances in diagnostic testing available to racecourse vets. PET scanners, bone scanners, MRI scanners and CT scanners are available at several tracks In America, genetic testing for sudden death is taking place, as is work to detect horses likely to develop arrhythmias of the heart.

Then there are systems that are minutely examining the stride patterns of horses while galloping to detect abnormalities or deviations from the norm. In America, a great deal of money and time is being spent developing a camera-based system and, in parallel, an Australian-US partnership is using the biometric signal analysis that is widely used in other sports.

The company – StrideSAFE – is a partnership between Australian company StrideMASTER and US company Equine Analysis. They make the point that, while pre-race examinations that involve a vet trotting a horse up and down and looking for signs of lameness, can play a useful role, many issues only become apparent at the gallop.

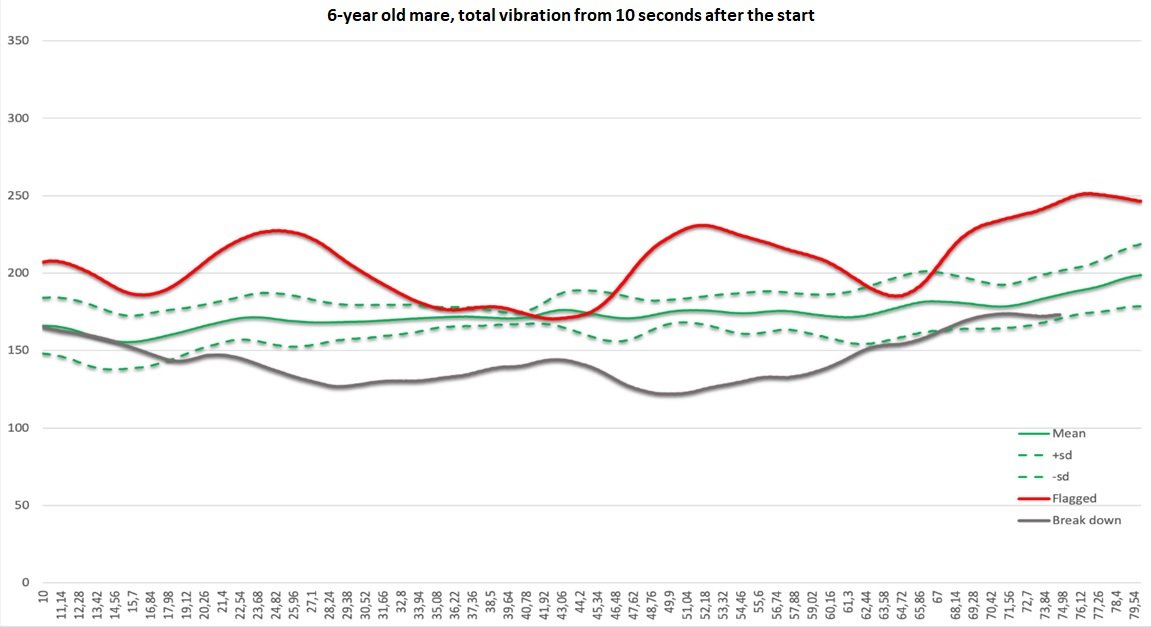

There are, in any case, limitations to what is discernible to the naked eye, which works at only 60 hertz. StrideMASTER’s three-ounce movement sensors, which fit into the saddlecloth, work at 2,400 hertz, measuring movements in three dimensions – forward and backward, up and down and side to side, and building up a picture of each horse’s ‘stride fingerprint’.

In a blind trial, involving thousands of horses, 27 of which had suffered an injury, this system had generated a warning ‘red-flag’ for no fewer than 25 of them. The green lines in the centre of this diagram are this horse’s normal stride fingerprint; the red line was the deviant pattern that would have flagged up the potential problem, and the grey line was where the horse then sadly injured itself.

The ‘stride fingerprint’ of a racehorse

While the false-positive rate is impressive for such screening tools, another enemy of all predictive technologies is the false positive, and ways need to be found to take action on the findings without imposing potentially unnecessary restrictions on horses’ participation. At present, the StrideMASTER system is typically throwing up three or four red flags for runners at an Australian meeting—more in America.

A study in the spring by the Kentucky Equine Drug Research Council, centering on Churchill Downs, will seek to hone in on true red flags and to develop a protocol for subsequent action. David Hawke, StrideMaster managing director, expands, “Protocols will likely vary from jurisdiction to jurisdiction, depending on the imaging modalities available. At Churchill Downs, they will have a PET scan, and we will be going straight from red-flag to PET scan.”

There will be other approaches available to regulators involving, for example, discussion with the trainer, a requirement for a clean vet’s certificate, or perhaps for a normal ‘fingerprint’, before racing next.

CONCLUSIONS

There is a need for continued investment and resource allocation by Racing Authorities. But the will would seem to be there. In Britain, €7M from betting will, over the next three years, fund an extensive array of no fewer than 26 horse welfare projects, covering such matters as education and support for re-homers, analysis of medication data and clinical records, fatalities occurring off the track, ground/going research and obstacle improvement and development. That is a serious statement of intent and an illustration of just how high in importance the welfare of racehorses has now become.

Of course, not all racing nations have the resources to conduct such research. It will be vital, therefore, that the lessons learnt are shared throughout the racing world. In Europe, this is where the EMHF will play a vital role. The federation has always had, as primary aims, education and the adoption of best practice across its membership.

The hope must be that, through all these measures and many others in combination, we can assuage the concerns of the public sufficiently to retain our social licence. But let our ambitions not rest there. We must also strive to shift the debate, to move onto the front foot and invite a focus on the many positive aspects of racing, as an example of the partnership between man and horse that brings rich benefit to both parties.

Elsewhere in this issue, there is a feature on racing in Turkey, and it was the founding father of that country, Kemal Ataturk, who famously said:

“Horseracing is a social need for modern societies.”

We should reinforce at every opportunity the fact that racing provides colour, excitement, entertainment, tax revenues, rural employment, a sense of historical and cultural identity and much more to the human participants. It is also the very purpose of a thoroughbred’s life and rewards it with ‘a life well lived.’

We have a lot more to do, but let’s hope we can turn the tide of public opinion such that people increasingly look at life as did Ataturk.